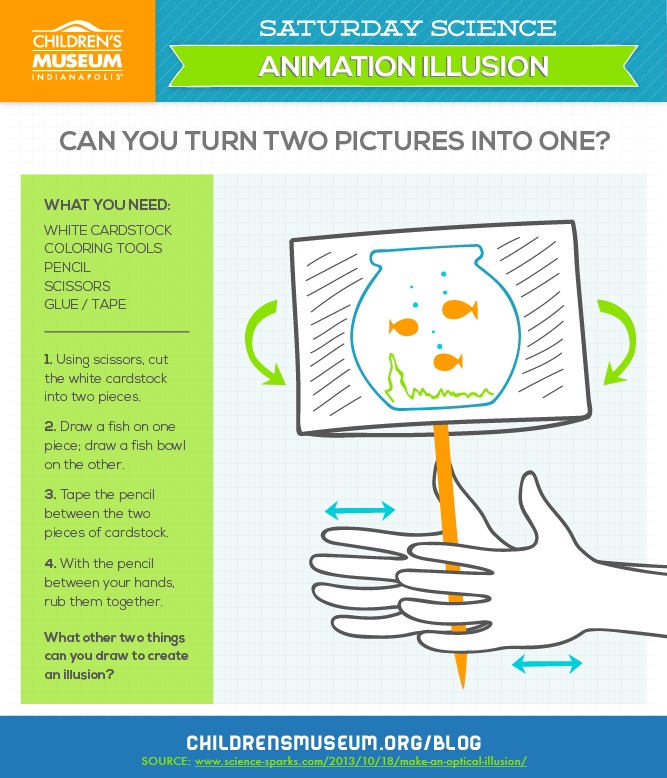

Okay, so cartoons are awesome. I think we can all agree on that. Sure, not all cartoons are awesome (I’m looking at you, Yogi Bear! You leave those pick-a-nick baskets alone!), but the idea that someone can draw stuff and make it seem like it’s moving is so insanely cool. You may have experimented with this idea yourself if you’ve ever tried to draw a flipbook. If you haven’t, great, you’re in the right place. Because today’s Saturday Science takes the principle of animation and boils it down to its basics. See, cartoons are made of separate drawings called “cels,” and it only really takes two to tango. Two cels, that is. You’re gonna use some basic supplies to create a very simple two-cel cartoon that seems to become one single image when you spin it around!

Materials

- 3x5 note cards or white cardstock

- Colored pencils

- Scissors

- Tape

Process:

- If you’re using cardstock instead of note cards, use your scissors to carefully cut them into two equal-sized pieces.

- Use your colored pencils to draw an empty fishbowl on one of your cards.

- Now draw a few fish on your other one (in the place where the fishbowl is on your first card).

- Tape the pencil between your two drawings so they’re opposite each other.

- Place the pencil between your two outstretched hands.

- Rub your hands back and forth to make the pencil spin!

- Observe what’s happening. What do you see?

Summary

If you taped everything right, you should have seen something pretty cool: as you spun the pencil, the fish appeared to be inside the fishbowl. They’re definitely not, so what’s going on? Basically, you just created an illusion, and all cartoons are just that: really fancy illusions. When drawings that are just a bit different are played quickly back-to-back-to-back, your brain interprets that as motion. This isn’t only true of animation; live-action movies and TV work the same way. Each separate image is called a “frame,” and they’re played fast enough that your brain can’t see that they’re all separate and still. In movies it’s usually 24 frames every second, while TV sometimes does 36 or 54.

Your little 2-cel cartoon did something similar, but instead of moving, the pictures appeared to combine with one another. The rapid motion back and forth caused your brain to combine them into a single smooth drawing.

When you're watching animation (or movies in general), your brain is doing some fancy footwork to interpret things as moving, and we know that for the illusion to really work you need at least 10 frames per second. Other than that, though, scientists still aren’t 100% sure what’s going on in your brain that makes it see the still images as motion.

It does work, though, so use some more notecards and try out some other drawings. What else can you think of to combine using your pencil and your imagination?

Want more Saturday Science? See all of our at-home activities on the blog or on Pinterest.

(

(